Art, Mentorship, and States of Siege

By: Kristi M. Wilson

By: Kristi M. Wilson

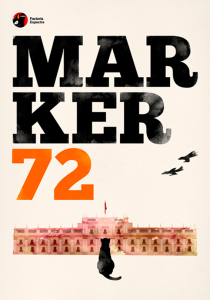

Miguel Ángel Vidaurre Marker ’72: Cartography of a Faceless Filmmaker. Chile, 2012.

Marker ’72: Cartography of a Faceless Filmmaker, produced by Factoría Espectra, is an essay-style documentary about the groundbreaking French filmmaker Chris Marker’s encounter with Salvador Allende’s Chile in 1972, his subse-quent mentorship of Chilean director Patricio Guzmán (The Battle of Chile), and his impact on the Chilean film community after the military coup of 1973. A legendary recluse and the director of enigmatic film classics such as La Jetée (1962), A Grin Without a Cat (1977), Sans Soleil (1983), and AK (1985), Marker arrived in Chile as part of the production team for the filming of Costa-Gavras’s political thriller State of Siege. According to Guzmán, in spite of the fact that State of Siege turned out to be one of the largest film productions in Chilean his-tory, Marker had not come to film anything with Costa-Gavras; “he just wanted to see Chile.”

Allende’s victory brought well-known people from around the world to Chile. As the documentary filmmaker and director of the Chilean School of Cinema Carlos Flores jokingly suggests in the film, Chile saw an influx of all types of people, from well-known hippies to CIA agents. Marker ’72 features an impressive array of archival footage, including excerpts from Allende’s final speeches. A particularly memorable archival sequence features two foreigners who went to Chile in sympathy with Allende’s movement. Dean Reed, a North American musician known as “El Elvis Rojo” (Red Elvis), is shown performing to large crowds, followed by television footage of an interview in which he says, “It was here in South America, in Chile, that I first saw the enormous injustices that exist. A tiny minority of people possesses all the privileges, hold all the wealth in their hands, while the vast majority live in misery under a dictatorship.” He is also shown speaking out against North American massa-cres in Vietnam and symbolically washing blood off of the U.S. flag in a Chilean plaza. Another foreigner, the French philosopher and academic Régis Debray (author of The Chilean Revolution), is featured on his return to France after Pinochet’s coup. Archival footage of Pinochet’s soldiers arresting and tear-gas-sing protesters and spraying them with fire hoses is juxtaposed with clips from Costa-Gavras’s famous Westerns and scenes from State of Siege, a film about military death squads and leftist guerrillas in Uruguay filmed in Chile on the eve of the coup. At a time when, as Flores suggests, “the ghost of military inter-vention fluttered everywhere,” the line between fiction and reality could not have been grayer.

Marker ’72 is characterized by vignette-style interviews with Guzmán, Flores, Sylvio Caiozzi, Pedro (Peter) Chaskel, and Jose Pépe Roman, all of whom reflect upon the film community in Chile just before and after the coup and the bonds that were forged between Chilean and French filmmakers. The interviews are punctuated with quotes from European filmmakers such as Alain Resnais, excerpts from foundational Latin American film texts such as Julio García Espinoza’s “Toward an Imperfect Cinema,” and shots of people reading the narration from a variety of Marker films and interviews. Each vignette begins with a quote and the same illustration of the back of a small black cat, comically referencing the prominence of cats in at least two of Marker’s films.

The phrase “You never know what you are filming” runs like a mantra through the film, suggesting that appearances can be deceiving. This idea oper-ates on multiple levels and is complicated by the aura of mystery surrounding the figure of Chris Marker. None of the filmmakers interviewed in the film can remember exactly what he looked like, other than that he was tall and skinny. The thickest description of him—by Saul Yellin—remains elusive: “thin, gothic, diabolic, well-respected.” Georges Sadoul suggests that Marker’s real name was not “Christian” and that it was difficult to determine the date and place of his birth. He posits that Marker could have been born in Peking, on Monk’s Island (Norway), or in Ulan Bator (Mongolia) and reminds viewers that he rejected interviews and did not allow himself to be photographed. Resnais had this to say about Marker: “Of course his name was not Marker. This alias was a pen name he took in some way from detective Nick Carter’s names, and with respect to Monk’s Island, he is also not originally from there, it is a pure inven-tion of his editor.” There are some solid, crucial bits of information that emerge in the film about Chris Marker, however. Guzmán describes him as a solitary man who, like a good father, wanted his students to forge ahead and work on their own.

Guzmán explains that Marker’s phrase, “You never know what you are film-ing” refers to a time at the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki when Marker was shoot-ing Olympia 52. Marker thought he was filming a member of the Chilean equestrian team when in fact this man became one of four torturers on Pinochet’s military board. Marker ’72 reaffirms the importance of film as a witness or a window on the future. Marker sought Guzmán out after viewing his first fea-ture-length documentary about the first year of the Unidad Popular (El Primer Año/The First Year) at a small film festival put on in conjunction with a United Nations event in Chile, and he never abandoned him. Guzmán recalls Marker’s saying on their first meeting, “I wanted to make a film about Chile, but since you’ve already done it and I saw it two days ago, I’ll buy it from you.” Guzmán sent a copy of the film to France, where Marker edited it down to 90 minutes for international distribution, had it dubbed in French using celebrity actors such as Yves Montand, Simone Signoret, and François Perier, and saw that it was released in a respected theater. While Marker was already known in Latin America for La Jetée and essays written about him in publications of the Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos, this was the start of Guzmán’s emergence on the world stage.

Marker continued to support Guzmán both in Chile and in exile during the dictatorship. Guzmán relays a story about complaining to Marker about the scarcity of film supplies in Chile and shortly thereafter receiving a shipment of 44,000 feet of new Kodak film stock from France. He had never seen so much film stock and literally passed out when it arrived. In no uncertain terms, Guzmán says that he owes the production and success of The Battle of Chile to Chris Marker and the Cubans, who welcomed him as a filmmaker for six years during his exile.

Chris Marker’s words at the end of the film appear as a harbinger of sorts for the current digital age. In a 1996 interview with Dolores Walfisch (1997), Marker looked toward the future of filmmaking:

A manifesto for a kind of film, one of many possible types. That’s it. To call it something else would be silly. You could never do Lawrence of Arabia like that, or Andrei Rublev, or Vertigo. But we have the means, and that is something new, for a way to make movies that are intimate and lonely—the process of making movies in communion with oneself, The way a painter works, or a writer. Now it doesn’t just have to be experimental. The concept of my comrade Astruc, of the camera as a pen, was just a metaphor. In his day, the most humble film product required a laboratory, an editing room, and money. Now a young filmmaker just needs an idea and a small team to prove himself. He doesn’t need to flatter producers, television networks, or committees.

Marker, one of the world’s most fiercely independent filmmakers, passed away in 2012. His legacy as an uncompromising artist and mentor to many up-and-coming filmmakers lives on. Marker ’72: Cartography of a Faceless Filmmaker is the fruit of an intergenerational mentorship that has survived the ebb and flow of military dictatorship.

REFERENCE

Walfisch, Dolores

1997 “Interview with Chris Marker.” Vertigo 1 (7).

Kristi M. Wilson is an assistant professor of rhetoric and composition and affiliate assistant profes-sor of humanities at Soka University of America.

LATIN AMERICAN PERSPECTIVES, Issue 204, Vol. 42 No. 5, September 2015, 269–271

DOI: 10.1177/0094582X15587482

© 2015 Latin American Perspectives