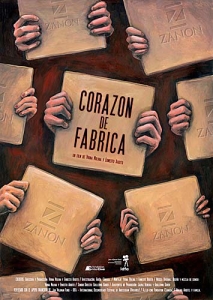

Despite the widespread perception of a turnaround in the Argentine economy in recent years and the institutionalization of popular movements, an ongoing workers’ struggle to lift local factories out of bankruptcy continues to inspire sectors of the Argentine population. Virna Molina and Ernesto Ardito’s Corazón de fábrica (Heart of the Factory, 2008) is not only a revealing account of workers’ reactions to the economic meltdown of 2001 but a multifaceted meditation on the political principles involved in the reorganization of a ceramic factory in the southern province of Neuquén. Corazón de fábrica attests to the pernicious impact that neoliberal policies have had on Argentine families, affecting every aspect of their lives: education, health, transportation, and, primarily, employment.

Despite the widespread perception of a turnaround in the Argentine economy in recent years and the institutionalization of popular movements, an ongoing workers’ struggle to lift local factories out of bankruptcy continues to inspire sectors of the Argentine population. Virna Molina and Ernesto Ardito’s Corazón de fábrica (Heart of the Factory, 2008) is not only a revealing account of workers’ reactions to the economic meltdown of 2001 but a multifaceted meditation on the political principles involved in the reorganization of a ceramic factory in the southern province of Neuquén. Corazón de fábrica attests to the pernicious impact that neoliberal policies have had on Argentine families, affecting every aspect of their lives: education, health, transportation, and, primarily, employment.

The film centers on a popular uprising of workers at the privately owned Zanón ceramic tile factory who resisted eviction when the factory closed its doors in the midst of the economic crisis. The workers appropriated the factory, created a cooperative, and renamed the company Fábrica sin Patrones (Factory without Bosses—FASINPAT). The long opening sequence, which features a group of schoolchildren observing the process of production, serves as an allegory for the mixing of earth and labor to create goods for the community. It is a rousing sequence, full of hope for the workers’ aspirations of rebuilding the country’s neglected industrial infrastructure in the aftermath of the crisis. Corazón de fábrica stresses the important work these collectives have done to educate their communities about processes of production and the fundamental role workers must play in determining the conditions of their labor. Molina and Ardito are seasoned filmmakers, and it shows. The pair directed the award-winning feature Raymundo (2003), an inspiring homage to the influential documentary director Raymundo Gleyzer, who was disappeared by the last dictatorship on May 27, 1976.

Several of the essays in this issue refer to Gleyzer’s groundbreaking documentary work and its influence on contemporary filmmakers.

There are at least two versions of Corazón de fábrica, one of them 129 minutes long and the other 58 minutes. Latin American Perspectives is making available the latter version. Both are valuable testimonies of the arduous process of reaching decisions collectively. Without a doubt, this is why the film was screened for protesters at Occupy Wall Street. More important, with this film we learn about the strategies workers employed, sometimes haphazardly, to resist eviction and reorganize the factories— strategies that often entailed risking their lives and those of their families. Such everyday heroism constitutes a defense not only of employees’ rights in Argentina but of the

rights of workers all over the world.

Readers can watch Corazón de fábrica by visiting the LAP web site:

http://www.latinamericanperspectives.com